The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale

The government can’t get my personal information without a warrant . . . right?! . . .

Contrary to popular belief, the government can and does acquire individual data without a warrant, and this practice is on the rise. The intermediary in this process? Data brokers. These entities, which you’ve most likely never heard of, have become a fundamental part of the digital economy. (In excess of $200B in 2022)

These Data Brokers collect, process, and sell extensive personal information about billions of people worldwide–including virtually all American citizens. But it's not just commercial entities that utilize these gold mines of your personal information; government agencies, including law enforcement, are among the customers of data brokers, adding a–rather convoluted–layer to the existing web of privacy laws, government operations, and market dynamics.

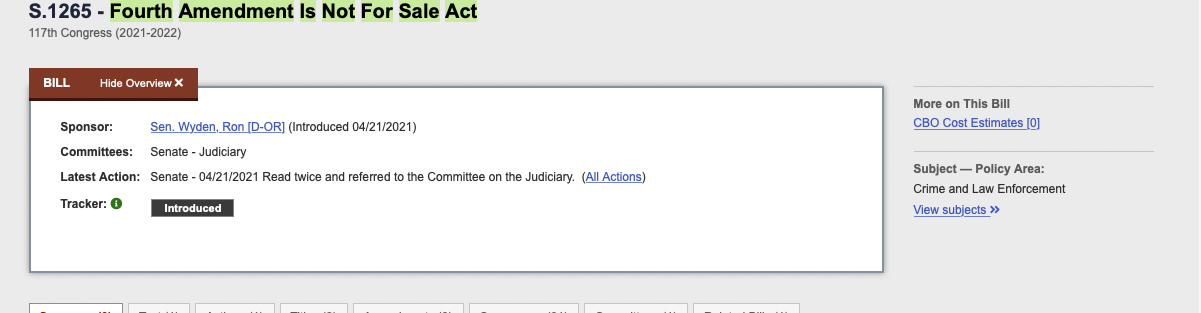

A bill named the "Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act," is set to change that. The legislation's stated aim is to reinforce privacy laws and limit law enforcement and intelligence agencies' ability to acquire customer records without explicit legal authorization. The bill delves into intermediary internet service providers' roles, amends existing sections of title 18 in the United States Code, and asserts that our fourth amendment rights should not be for sale.

There is a balance to be struck between individual privacy and collective security, but we certainly haven’t found that balance yet. Could this be the solution?..

What Is a Data Broker?

Data brokers, also known as information resellers or data vendors, are businesses that collect information from a wide range of sources, process it to provide insights, and then sell that information to other entities. These entities can include businesses, marketers, researchers, and yes, even government agencies.

What Information Do They Collect on Me?

Data brokers collect a wide variety of information on individuals, and it varies significantly between brokers based on their specific focus and the services they offer. However, some common categories of information often included in these files are:

Image Source: Reader’s Digest

Identifying Information: This includes basic information such as names, addresses, email addresses, phone numbers, and social security numbers.

Demographic Information: Information such as age, sex, race, occupation, education level, marital status, and number of children may be included.

Financial Information: This may include income level, credit score, credit card usage, loan information, and other financial data.

Purchasing Behavior: Data brokers often collect information on individuals' purchasing habits, such as what products they buy, where they shop, and how much they spend.

Online Behavior: This can include web browsing history, search queries, social media activity, online purchases, and other digital footprints.

Health Information: While protected health information is generally safeguarded under regulations like HIPAA in the United States, some data brokers may still collect health-related data, such as over-the-counter drug purchases, interests in certain health topics, or participation in certain health-related activities (though the FTC is currently working on this).

Public Records: This can include property records, court records, voter registration, and other publicly available information.

Geographic and Travel Data: Information related to an individual's location, travel history, or patterns can also be collected. You know, Google Maps.

Lifestyle and Interests: Information about hobbies, lifestyle choices, memberships to clubs or organizations, and other personal interests can be part of these profiles.

Image Source: Privacy Bee

Who Are the Largest Data Brokers?

Acxiom: data across 62 countries and 2.5 billion consumers. This is about 68% of the world’s internet population.

Epsilon Data Management: provides data solutions to businesses worldwide. One aspect of this involves a consumer database consisting of details from millions of households

Oracle: Oracle's data brokerage division, Oracle Data Cloud, claims to have profiles on 2 billion consumers.

Experian: As one of the leading credit reporting agencies, Experian holds data on over 1 billion individuals and businesses globally. Their databases provide a comprehensive picture of consumers’ financial behavior.

Equifax: Equifax is another significant credit bureau and data broker with information on over 800 million individuals and 99 million businesses worldwide. Like Experian, its databases cover extensive details about consumers' financial behavior.

CoreLogic: CoreLogic focuses on property data. While I couldn’t find numbers on how many individuals' data they hold, their databases cover 99% of U.S. property records.

What About the 4th Amendment, And, You Know, Other Laws?

Data protection laws, like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in California, among the other nine states that have passed data privacy laws, do provide some protections for consumers. For example, they may require companies to disclose what data they collect and allow consumers to opt-out (or opt-in in the case of GDPR and CCPA). However, these laws have jurisdiction limitations and may not fully prevent data sales to government agencies.

This consumer data marketplace allows government agencies to bypass laws—and the 4th Amendment in the view of some—that would otherwise restrict their ability to collect certain types of data. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. This means that the government cannot search you or your property without explicit permission from a court, like a warrant. A warrant is a legal document issued by a judge or other authorized official that allows law enforcement agencies to perform specific actions that could infringe upon an individual's privacy, such as searching a person's property or seizing evidence. But when data is bought rather than directly collected by the government, it's not clear that these protections apply.

The Third-Party Doctrine

When law enforcement agencies buy data from brokers, they may be able to sidestep the traditional warrant process because of the Third-Party Doctrine. The Third-Party Doctrine is a legal theory that holds that people who voluntarily give information to third parties, such as banks, phone companies, internet service providers, and data brokers, have "no reasonable expectation of privacy." The doctrine originates from two Supreme Court cases in the 1970s, United States v. Miller and Smith v. Maryland, which ruled information voluntarily given to third parties was not protected by the Fourth Amendment.

The doctrine effectively allows law enforcement agencies to obtain certain types of information from third parties without a warrant, i.e., information purchased from data brokers. In the digital age, where vast amounts of personal information are held by third parties, the doctrine has become increasingly broad and increasingly controversial. Critics argue that it has been stretched beyond its original intent, undermining privacy rights by allowing collection of personal data that the government, or no one for that matter, should have.

This critique of the apparent lack of 4th Amendment Rights because of new technology has been addressed by the Supreme Court, but mostly in the context of physical location tracking (Carpenter v. U.S.) and search of a device itself rather than data collected off-device (Riley v. California). The court has yet to address this in the context of data brokers. . . but the third-party doctrine requires the party to voluntarily give information over to the third-party.

This is one of the key questions addressed in Carpenter: Am I really volunteering my information, or is the ”choice” removed ipso facto if modern life requires the technology? Can you really live in today’s world without a cell phone?

Image Source: Congress.gov

How Does The Bill Address The Problem?

Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, Section by Section

The "Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act" aims to strengthen privacy laws by preventing law enforcement and intelligence agencies from obtaining customer records in exchange for anything of value, addressing intermediary internet service providers, and amending existing sections of title 18 in the United States Code. Introduced by Senator Wyden, it seeks to protect personal data from unauthorized access by requiring a court order for certain disclosures and limiting the immunity of those who assist government entities without one.

Section 1 - provides the bill with its title, "The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act."

Section 2 - introduces new definitions and prevents law enforcement and intelligence agencies from acquiring customer or subscriber records from third parties in exchange for anything of value.

Section 3 - necessitates a court order for third parties to disclose customer or subscriber records or certain information to governmental entities.

Section 4 - defines "intermediary service provider" as any company or operator that handles, stores, or manages communication data, either directly or indirectly. It prohibits these entities from disclosing contents of a communication or specific records about subscribers or customers to anyone.

Section 5 - limits the scope and means of acquiring location data, web browsing history, and internet search history for foreign intelligence purposes.

Section 6 - limits the civil immunity of individuals or entities assisting the government without a court order.

So, Will This Solve the Problem?

There's an ongoing debate about whether current laws sufficiently protect privacy and how they should be updated to reflect the realities of the digital age. While state-level legislation such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and similar laws in nine other states have made strides toward safeguarding consumer data, they fall short when it comes to data brokers. So, in my opinion, yes. This bill does seem to do what its stated intentions are: limiting government access to personal data without a warrant.

Parting Thoughts

Although the bill advanced unanimously out of the house committee, there are two sides to this argument. Civil rights advocates argue that stricter regulations or new interpretations of the Fourth Amendment are needed in light of new technology to protect privacy, while the other side argues that government access is necessary for effective intelligence and law enforcement and that adequate safeguards are already in place; which brings us to the most significant hurdle over which this bill will have to super-jump: opposition from the intelligence community.